امامی در کلیسا

For human beings, in their needs and potential

Religion in the service of humankind

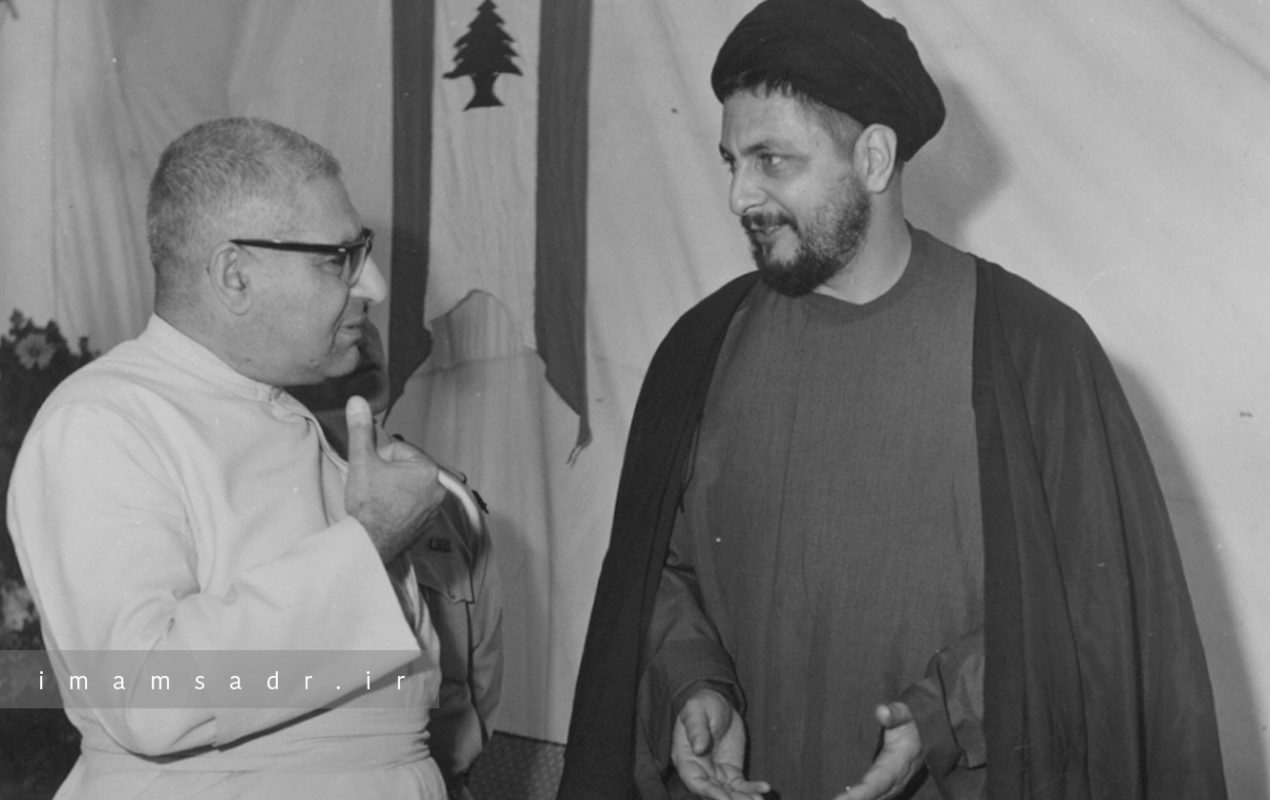

A speech made in the Capuchin Church on 1975/2/19 and published in the book entitled “Islam, a deep-rooted doctrine” in 1979:

Translation: Michael K. Scott

Revision: Gareth Smyth

We praise and thank you, Lord and God of Abraham and Ismail, God of Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad, Lord of the downtrodden[۱] and God of all creation. Praise be to God, who secures and provides support to the downtrodden, frees the just, elevates the humble and humbles the arrogant; who brings down a monarch and delivers his replacement; destroys the tyrant and castigates the oppressor; helps fugitives, and punishes the despot[۲]. Praise be to God, who hears the cry of the desperate.

We praise you, our Lord, and stand before you seeking your care. We congregate under your guidance, our hearts united in your love and your mercy. We meet here in your midst in one of your houses of worship, during period of fasting for your sake, our hearts yearning for you, our minds deriving light and guidance from you, and, on your invitation, we walk side by side in the service of your creation, to meet around a just testament[۳], for the happiness of human beings, who are your representatives. Our destination is your door, and we turn in prayer towards your mihrab[۴].

We have come together for the sake of mankind[۵], for whose sake religions, one original religion, are revealed, to bring good tidings and bear witness to God delivering humankind from darkness into light, rescuing people from their many weighty, divisive differences and teaching them the right conduct for the sake of peace.

Religions were once one, and they served one objective: to call people to God and to serve humankind. For religions are the expression of the one truth. They quarrelled when they came to serve themselves, when their self-interest grew so that they lost sight of their objective. Conflicts intensified and differences multiplied, increasing the plight and suffering of humankind.

Religions, when they were one, worked to fulfil the one objective of battling worldly gods and tyrants while providing help to the vulnerable and the oppressed, two aspects of the one truth. When religions triumphed, and the oppressed triumphed with them, tyrants were quick to don the mantle of religion and use it to reap rewards, for they had learnt to rule and to brandish a sword in the name of religion. This exacerbated the ordeal of the oppressed and the predicament of religions, and gave rise to all manner of differences between them. Wherever a dispute is found, there too are found exploiters. Where differences appeared between religions, it was because of their exploiters’ vested interests.

Religions were originally all one, in the beginning, which is God, who is one. The objective, which is the human, is one; and the path, which is this, our universe, is one. When we lost sight of the objective and abandoned our service of the human, God neglected us, and He took distance from us. We found ourselves fragmented into small parts, sects, and groups, and as punishment He cast us into the ways of harm and misery, so that we fight among ourselves and throw our universe into disarray, serve narrow interests, worship gods inferior to the one God, and tear the human asunder.

And now we return to the path; we return to the human; so that God will return to us; we must turn again to human suffering and save ourselves from the wrath of God. We must again seek the human − which was destroyed, torn apart − so that we come together and embrace the whole, and thereby meet God, so that all the religions shall again be one.

“We have ordained a law and assigned a path. Had God pleased, He could have made of you one community; but it is His wish to prove you by that which he bestowed upon you. Vie with each other in good works, for to God shall you all return and He will resolve your differences for you.”[۶]

Now, in this church, in times of fasting, in a sermon that committed senior figures[۷] have invited me to give, I find myself travelling a road alongside you. I find myself preaching, both discoursing and being counselled − speaking with my voice and listening with my heart[۸]. History teaches us, and history testifies, that Lebanon is the land of human encounters, homeland of the oppressed, haven for the frightened. In this sublime setting, with its heavenly horizons, we can respond to the original celestial summons, for we are closer to the springs of the divine.

Here is the Lord, loving in anger, His voice high: “No! God’s love shall not meet with human hatred.”[۹] His voice loud in our conscience, in the last Prophet of mercy: “Never will one believe in God and Judgment Day, who is sated while his neighbour goes hungry.”[۱۰]

These two voices interact through the ages. They echo the words of the Pope at Lent: “Christ and the poor are one and the same.” In his famous encyclical Populorum Progressio[۱۱], the Pope calls for human dignity, just as the Messiah did in the temple. “They are sorely tempted to redress these insults to their human nature by violent means.”[۱۲] And he adds that the basest humanity is that of brutal despots who abuse the rights of kings and princes, steal the rights of workers, and conclude exploitative deals.

Does this pristine voice not differ little from the objective expressed in the Muslim tradition? When God says “I am God, always there with those whose hearts are broken, with the poor struck by illness, with the poor whom I aid and assist, with the needy to whom I provide relief…”?[۱۳]

How? Every effort to defend a right and to aid the oppressed is considered a struggle on the path of jihad[۱۴], a prayer at the minbar[۱۵]. It offers victory.

By means of these testimonies we can return to the human to distil the forces that destroy and the forces that divide. The human being is a divine gift, a creature created in the image of his creator and given to share in His qualities, God’s deputy on earth[۱۶]. H/she, the human being, is the foundation of existence, the beginning and the end of the community and of society, the prime mover of history and its engine. She is equivalent to and the equal of the sum of her capacities and energies ‒ not only when, in this century, philosophy and physics confirmed exchange and transformation between material substance and energy, but also as religions and scientific experiments have long shown: “Each man shall be judged only by his labours.”[۱۷] Human work is eternal; humans who do not reach for wide horizons through their labour are not worth much. Only to the extent that we safeguard and develop human energy[۱۸], do we honour the human and give her eternal life.

Faith, in its heavenly spiritual form, gives human beings the possibility of infinite sensitivity and aspiration, and keeps hope constantly alive. When faith is secure, it removes anxiety and worries; difficulties are lifted. Faith adjusts human relationships, with other humans and with all other creatures. Faith gives human beings glory and beauty; it repairs, protects and sustains them. It requires self-preservation and conservation. It affirms that faith itself cannot exist without a commitment to serve humanity.

The entire energy of humankind, and the energy of each and every human being, must be conserved and nurtured. It is on this basis that human striving for perfection and self-fulfilment has gone hand in hand with the divine and prophetic mission, from the earliest days of the religious call to the recent appeal of the Holy Father: to be authentic, human development must be well rounded; it must foster the development of every human being, and of the human being as a whole[۱۹]. This is why we find theft prohibited in the commandments. It is a violation, a usurpation of human energy and its fruit − and look today, we see theft in the form of economic exploitation and monopoly, supposedly to lead to prosperity and industrial development, with ways of operating that impose artificial consumer ‘needs’ upon people, giving them a fraudulent desire for ever-greater consumption. Today’s ‘needs’ do not flow from the human soul or self, they are fostered through commercialised media subservient to those who control the means of production.[۲۰]

Every day thrusts a new need upon mankind, or develops a new need from an existing one, taking control of all human energy and transforming so much of it that one ceases to choose how to expend it, or becomes unable to expend it as one wishes. We are witnessing a profound change that obstructs and repels the energy of humankind, destroys and shatters it. These forces remain essentially the same, despite the disparity of their shape or form, and despite the great extent of their ‘development’.

Religion has fought, also, against lies and hypocrisy, and against vanity and pride; when we observe the roots of these traits, we understand better their impact on the energy and potential of individuals and groups. Lying falsifies facts and dissipates the energy marshalled to enable healthy exchange between human beings, and the energy that gives the opportunity to grow. Lying stymies energy, distorts human exchange, and wastes potential. Vanity and pride freeze and paralyse human relations. When people come to feel self-important and vain, they think that they are self-sufficient, so they cease to receive and they then fail to be complete or fulfilled. Others, in turn, will stop receiving from them. Without giving and taking there is only death, the demise of energy and capacity, the death of human abilities and capacity. It is the same with traits similar to deceit and pride.

Freedom, in contrast, offers an environment enabling the growth of human potential and the blossoming of a person’s talents and gifts. Freedom has long been subject to assault, often violated on diverse pretexts. In so far as it enables the growth of human faculties, energy and aptitude, freedom is the source[۲۱] of all human powers. There have been bitter battles for freedom. When freedom is robbed from a person, that person’s potential, and the whole community’s, are subject to the whim of the usurper. People are diminished, shrunk to the level forced on them by the usurper. With the intensity and scope of freedom offered to human beings so diminished, and their creative lifeblood drained, both the individual and the community − society at large − become stunted. When a person rejects curtailment and bloodletting, and, as we strive with her, in accordance with our faith, to limit or put an end to the tyranny of this divisive and destructive oppression, we are together defending long-term human potential and dignity, whatever historical form is taken by the attempt to undermine freedom.

From despotism to colonialism, from feudalism to the [modern] repression of freedom of thought [۲۲], history is full of those claiming custody over people they say are ignorant and lack understanding. From neo-colonialism to the imposition of ideological beliefs on individuals and peoples through economic, cultural or intellectual force – even policies of deliberate negligence[۲۳] and marginalisation, depriving people, some people, of opportunity, and withdrawing opportunity from whole regions, some regions − there have been many measures restricting freedom, destroying human potential and depriving people of heath, mobility and development.

And then there is wealth, this greatest of idols and which the Lord Jesus considered more prohibitive of entry to the kingdom of heaven than the size of a camel in trying to pass through the eye of needle.[۲۴] Wealth is temptation and affliction, even though it can be used wisely in its appropriate place to partake of grace and mercy. When, instead of God, wealth becomes the holy of holies pursued by the worshipper, who becomes trapped in its orbit, it grows at the expense of other needs of individuals and the community. And it takes on a destructive, fracturing power that has a profound impact upon people’s lives. The large consumes the small.

It is much the same way with any human need, when it grows in a way detrimental to other human needs. Let us consider the category of ‘desire’ or ‘lust’: all such desire is a human drive, an engine that propels humans through life. But when it grows at the expense of other human needs, it turns catastrophic and brings disaster. This is why an enormous responsibility attaches to enjoying property, wealth, prestige, influence and all other areas of human activity and capabilities.

Faith keeps a link between God and humans, it is continuously present and needs persistent attention. Exclusion and rejection of faith as a basis for modern culture and civilization renders culture vulnerable to this imbalance. When we review the history of our modern civilization, we see human beings becoming more inclined to pursue wealth at the expense of other objectives. Because politics, governance, commerce and urbanisation have not been grounded firmly in faith that adjusts and tempers them to serve everyone and to avoid destroying and fragmenting people’s lives, they have expanded over time into colonialism, wars, unfair markets, and militarised peace − a peace that rests on armed deterrence.[۲۵] This has cast humanity in its entirety fluctuating between hot and cold wars, between periods of dressing wounds and peace, loaded and primed.

Further, the love of self, the fuel of perfection that humans can draw upon to achieve their aspirations, this fine thing that serves human needs, can also be problematic, as when it grows unchecked inside an individual and morphs into self-worship. Here is the source of conflict, racial discrimination, contempt of others, bitter struggles ‒ from the smallest units within society to international relations. This conflict entails multiple episodes. Although the arena for these circles of conflict is one and the same, the size and scope of the circles vary.

People have wrongly considered such conflict or struggle to be an integral part of creation − an error that is a consequence of self-love growing to the extent it transforms into self-worship. Individual selfishness can become collective selfishness. A group or a collective takes shape in the service of humankind, for a person in her very nature is a collective being who seeks to belong to society. Man has both dimensions − the personal or individual, and the collective. When selfishness takes on a collective meaning, the collective itself, the community, becomes selfish. Here the problem builds into wider frameworks: the selfish self becomes a familial selfishness, which inflicts much evil upon humankind, expands into despotic tribalism, and undermines the whole system with myriad consequences. We then see confessionalism[۲۶] or sectarianism, by way of selfishness, upending heaven and earth, and emptying religion of sublimity, compassion, coherence and tolerance.[۲۷] This expression of sectarianism buys and sells values at all sorts of prices, and forges them into a patriotic nationalism of selfishness. Patriotism may well be one of the most noble sentiments and motivations, yet it can become a racist patriotism when human beings are led to worship homeland and nation before God almighty. This is when human beings build the glory of ‘nation’ on the ruins of the homeland of others[۲۸], and found their civilization on the destruction and devastation of the civilizations of others, raising up their own people at the expense of others, and, as in the case of Nazi nationalism, burning the world over and over again.

We end up worshipping such expanded egoisms, we turn them into affliction and devastation; whereas original self-love, duty towards parents and love of family, and patriotic love of community and nation, are all among the finest callings of human life, as long as they are practised within appropriate limits. This explains the title chosen for this talk: ‘For human beings, in their needs and potential.’

Society that empowers the human being must be co-ordinated and harmonious, as a whole. The individual must be fully integrated and in tune with it. Whenever any particular human need exceeds or precedes other needs in society, whenever it is fulfilled at their expense, the situation turns unhealthy and noxious. It is no less harmful and unhealthy whenever an individual or an individual’s needs grow to the detriment of other individuals. Disaster strikes whenever one group or one group’s needs grow at the expense of another group or another group’s needs. Moderation is achieved by probing, exploring connections with others, to the point that one comes to feel the pain felt by others as one’s own pain. This is exactly the aim − and requirement – of fasting. Such moderation and balance guarantee the individual’s healthy and sound growth, together with the safe and sustainable growth of the collective.

Lebanon is our country, and Lebanon’s primary and ultimate wealth and capital is its human being. It is the human being who has written the glory of Lebanon through her effort, migration, thought, and initiative. It is this human being that must be preserved in this country. If other countries have wealth beyond human wealth, our wealth ‘beyond’ human wealth is also human.[۲۹] Our work in Lebanon looks for this direction, it seeks opportunities, through temples of worship, universities and institutions, to maintain human wealth through humanist administration and management, so that every human being, whichever part of the country they live in, enjoys their many talents, becomes fully human.[۳۰]

If we wish to preserve Lebanon and protect it, if we wish to put our patriotic fervour into practice, if we wish to practise our religious sensitivity through the principles just presented, we must then preserve the human beings of Lebanon, all of them, every one, in all of his and her capacities, and not only some of them.

In the Lebanon we live in, where everyday witnesses deprivation, this deprivation is caused by malpractice. Responsibility falls upon everyone. Forceful verbal expression in the service of human beings, as we heard in the blessed sermon[۳۱], is allowed to the extent it does not adversely impact the human being or subvert him.

The regions in which our fellow humans live[۳۲], like all humans in Lebanon, are a trust[۳۳] fixed to our necks, and fixed to the necks of the responsible authorities. South Lebanon, and all the regions of the country, are trusts to be preserved, by the will of God and the will of the nation. It is essential that we pay heed in our thought to practice and implementation. Wrong-headed thinking and misplaced investment are each double-betrayals of this trust − as they are both a form of corruption and involve missing genuine opportunities through wasting funds and undermining public rights. Privileges and perks, whatever form they may take, serve to differentiate and divide, no matter how they are packaged or labelled.

Our Lebanon, the country of human beings and of humanism, highlights the humane reality through the contrast lived today with the enemy, an enemy through which we can see the formation of a racist society that destroys and discriminates, financially, culturally, politically, and militarily. We even see the enemy distorting history, proceeding with the Judaization of the holy city of Jerusalem and disfiguring its historic monuments.[۳۴]

Our nation is not only something to preserve for God and for His human beings here. It must be preserved for all of humankind, for humankind in its entirety, so that its true expression is promoted worldwide in defiance of many false images. And we find ourselves facing the opportunity of a lifetime in the new episode that Lebanon has begun.

So let us meet, faithful men and women, let us meet for humankind, at the level of humankind, and at the level of every single human being − every human, our humanity, in Beirut, in the south, in Hermel, in Akkar, in the Beirut suburbs from Karantina to Hayy al-Sulum.[۳۵] The human being, every single human being, is never to be excluded from opportunity through being isolated, categorised or classified. Let us preserve humankind in Lebanon and Lebanon’s humanity, and preserve this country, the country of humankind. It is a trust of history and a trust of God.

May God’s peace and mercy be with you.

[۱] . Mustad‘afin is literally ‘weakened’ or ‘made weak’ and is often translated as ‘weak’ or ‘oppressed’. The exact word mustad‘afin occurs many times in the Qur’an, four times in Surah ‘Women’ (al-Nisa) alone (4.75, 4.97, 4.98 and 4.127). Other grammatical forms of the word occur even more often, as in Surah al-Qasas: “…it was our will to favour those who were oppressed in the land and to make them leaders among men, to bestow on them a noble heritage and to give them power in the land …” (Surah ‘The Story’, al-Qasas, ۲۸.۴).

[۲] . This is from a well-known Shia du’a, or prayer.

[۳] . ‘Just testament’ is a translation of kalimat sawa, a phrase in the Qur’an referencing the call of the Prophet to the “people of the book” (Surah ‘The ‘Imrans’, al-‘Imran, ۳:۶۴). The phrase, translated by NJ Dawood as ‘agreement’, also has connotations in Arabic and Islam of a set of just teachings and beliefs. “People of the Book, let us come to an agreement: that we will worship none but God, that we will associate none with Him, and that none of us shall set up mortals as deities besides God.” English translations of the Qur’an are from NJ Dawood, 2003 edition published by Penguin Classics.

[۴] . The mihrab is the central niche in a mosque that indicates the direction of Mecca, for prayer.

[۵] . In this text, given Musa Sadr’s views on gender, we have often used ‘humankind’, and the pronoun ‘she’ as well as ‘he’.

[۶] . Qur’an, Surah ‘The Table’, al-Ma’idah, ۵:۴۸. Some translations have ‘test’ rather than ‘prove’.

[۷] . Mas’ulin multazimin: the term refers to officials committed to a goal. Musa Sadr is speaking of the senior Catholic clergy.

[۸] . Atakallam bi-lisani wa usghi bi-qalbi – usghi is ‘listening carefully’.

[۹] . This probably refers to the Bible, John 13:34: “…I give you a new commandment, that you love one another.” Biblical quotations from New Revised Standard Version, Cambridge University Press 1989.

[۱۰] . While the text of the Qur’an is the same for Sunnis and Shi‘is, the concept of hadith differs. For Sunnis, hadith refers only to Prophet Muhammad’s sayings (or silence, or behaviour) as related by trusted tradents. For Shi‘is, hadith also includes the hadith of the Twelve Imams of the tradition. The most trusted compilation of Shi‘i hadith was made by Kulayni (died 941) and is known as al-Kafi (literally ‘sufficient’). This hadith, ‘ma aamana billah wal-yawm al-akhar man bat shib‘anan wa jaruh ja’e’, is related, for example, in Kulayni, Al-Kafi, Volume 2, p 668: we have used the 2000 edition, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Eslamiah, Tehran. This hadith is from the Prophet, and is common to Sunnis and Shi‘is.

[۱۱] . Populorum Progressio (‘The Development of Peoples’) was an encyclical on Christian social teaching issued in 1967 by Pope Paul VI. It stressed that economic development should benefit all humankind rather than a few, with fair wages and working conditions. Becoming pope in June 1963, Paul VI followed the direction set under his predecessor Pope John XXIII during the Second Vatican Council (October 1962-December 1965), which stressed aggiornamento (‘bringing up to date’), social justice and inter-faith discussions.

[۱۲] . Populorum Progressio, paragraph 30: “Lacking the bare necessities of life, whole nations are under the thumb of others…They are sorely tempted to redress these insults to their human nature by violent means.”

[۱۳] . Musa Sadr is citing a Prophetic hadith for the Sunnis, related in al-Hamm wal-Huzn (‘Grief and Sadness’). We have referenced this, hadith number 61, in the edition published by Dar Assalam Leltebaa’h Wannashr Wattawzi, Cairo 1991.

[۱۴] . ‘Jihad’ has become a worldwide word, defined in different ways, often as ‘holy war’. It comes from Arabic jihād, literally ‘effort’, and in Muslim thought, struggle on behalf of God and Islam. Musa Sadr emphasises nonviolent effort.

[۱۵] . The minbar is the raised platform in a mosque from which the prayer leader, or imam, addresses those congregated.

[۱۶] . See Surah ‘The Cow’, al-Baqarah, ۲:۲۹. The Arabic khalifa is variously translated as ‘vice-regent’, ‘deputy’, ‘caliph’ and ‘successor’. The last can imply that the human succeeds God, which is not the meaning of the Arabic. In the Qur’an, the word khalifa carries no political connotation.

[۱۷] . Qur’an, Surah ‘The Star’, al-Najm, ۵۳:۳۹.

[۱۸] . Taqah is ‘energy’, ‘power’ (even electric power), but also ‘capacity’ or ‘potential’.

[۱۹] . Musa Sadr is here citing Populorum Progressio, paragraph 14: “The development we speak of here cannot be restricted to economic growth alone…”

[۲۰] . In the 1960s and 70s Christian and Muslim thinkers alike were reacting − like Marxists, and with partly similar and partly different answers and approaches − to real or perceived growing inequality within and between nations: Christian and Muslim thinkers reached back to the egalitarianism of Jesus or Muhammad that long predated Marx. Musa Sadr’s sermon at the St Louis Cathedral well illustrates an emphasis on ethics, an area where ‘deterministic’ Marxism struggled.

[۲۱] . Umm, literally ‘mother’.

[۲۲] . Al-irhab al-fikri − literally ‘stifling the mind’.

[۲۳] . Siyasat al-ihmal. The notion of ‘deliberate negligence’ or ‘deliberate policy of negligence’ is almost self-contradictory, and yet it brilliantly encapsulates the Lebanese state’s treatment of ‘peripheral’ areas, including those inhabited mainly by Shia Muslims. The context would not have been lost on Musa Sadr’s Catholic audience, and yet his argument rests on universal rights and not sectarianism, situating the Shia in Lebanon within a consistent, overall framework.

[۲۴] . This refers to words of Jesus cited in the gospels of Matthew, Mark (10:24) and Luke (18:24). “Truly, I tell you, it will be hard for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven. Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Matthew, 19:23).

[۲۵] . Musa Sadr is referring here mainly to the ‘cold war’, rivalry short of armed conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union; but he is also alluding to the era being far from peaceful in much of the developing world, where great power rivalries cut across struggles against colonialism and for social justice.

[۲۶] . Musa Sadr here refers to the Lebanese system of ‘confessionalism’ (ta’ifiyya, from ta’ifa, religious group or sect). Confessionalisme is the French word used in Lebanon to describe the system during the Mandate (1920-1943), and corresponds to ‘communalism’ during British domination of India. While the religious sect/confession has roots in Middle Eastern antiquity, it was institutionalised in Lebanon during the Mutasarrifiyya (1865-1914).

[۲۷] . The context to this sermon − rising tensions in Lebanon weeks, days even, before the incidents that sparked the 15-year civil war – was surely felt by those attending and those who read about it in the newspapers the following day.

[۲۸] . This refers to Israel in particular. Despite Sadr’s criticism of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, then dominant in Lebanon, his criticism of Israel (which he called sharr mutlaq ‘absolute evil’) as a source of oppression never wavered.

[۲۹] . Musa Sadr is making a general point, although his audience might think of Lebanon lacking the mineral wealth of some regional countries, notably oil (Lebanon has more recently found offshore oil). While blessed with precipitation and verdant valleys, the Lebanese have always prized their creativity as seen in multilingualism, the arts and commerce.

[۳۰] . This is both a specific reference to relatively deprived parts of Lebanon, and an illustration of the general principle cited earlier: “The entire energy of humankind, and the energy of each and every human being, must be conserved and nurtured.”

[۳۱] . This is probably a reference to Jesus, as described in all four gospels, entering the temple and upsetting the tables of money-lenders and merchants. “He said to them, ‘It is written: “My house shall be called a house of prayer”; but you are making it a den or robbers.’” Matthew, 21:12-13

[۳۲] . Sadr probably refers to the south of Lebanon and to the Beirut suburbs, where poorer sections of the Lebanese population lived, mostly Shi‘i.

[۳۳] . Musa Sadr often mentions trust, amana, both a moral and legal concept. The roots of the word are Semitic, and continue in Western liturgy with ‘Amen’. Amin (trustworthy, fiduciary) and amana appear often in the Qur’an. It is also of common usage in law, where agencies and partnerships are based on trust.

[۳۴] . Israel occupied Jerusalem during the 1967 war. Meron Benvenisti, deputy mayor of Jerusalem from 1971 to 1978, wrote in 1995: “Although Jerusalem’s physical space was unified after the Six-Day War in 1967, the city’s psychological space did not merge with it…Segregation and alienation cut across all levels of communal interaction, from nursery to graveyard.” Meron Benvenisti, Intimate Enemies: Jews and Arabs in a Shared Land, University of California Press, 1995.

[۳۵] . Karantina is in northern Beirut, part of ‘east’ (mainly Christian) Beirut; whereas Hayy al-Sulum (the ‘Staircase Neighbourhood’) is south Beirut. Karantina was at the time of Musa Sadr’s sermon mainly a Palestinian camp, where poor Kurds, Syrians and Armenians also lived. In January 1976 Christian militias massacred at least 1,000 people, leading to a reprisal attack by Palestinians on the mainly Christian town of Damour south of Beirut, in which at least 500 were massacred. Hayy al-Sulum is part of Beirut’s ‘southern suburbs’, a once prosperous, semi-rural fringe that became home to Lebanese Shia displaced from the south by Israeli invasions in 1978 and 1982 or who just sought work in the capital.